I was reading the aidan_mclau essay about the Problem of Reasoners. The post is interesting but seems to fundamentally misunderstand reasoning, knowledge, and the limitations of systems constrained by their structures.

The post seems to be bearish on “domains without easy verification.”

Throughout this essay, I’ve doomsayed o1-like reasoners because they’re locked into domains with easy verification. You won't see inference performance scale if you can’t gather near-unlimited practice examples for o1.”’

The post explains how “o1,” like “reasoners” trained on RL, have hit a wall in many domains.

wordgrammar emphasizes the point of the essay with this

“Humans have wished since time immemorial that we might never have to work on menial tasks and spend all of our time studying more “meaningful” topics. Like art and philosophy. But if LLMs automate everything besides art and philosophy… won’t we be forced to study it? Hmm”

My question to the reader is, isn’t this to be expected?

To call what LLMs do “reasoning” still misunderstands what reasoning is. Reasoning is the ability to use induction and deduction. What is being referred to as domains with easy verification are deductive domains. Domains without easy verification are inductive domains. The trouble for many people and LLMs is that the base of all knowledge is inductive.

It would be nice if one could easily fit the entirety of the world into a closed formal system and pull out objective truths. For many reasons, this can never be the case.

Instead, to arrive at knowledge, one must interact with the world, learn cause and effect, form concepts from percepts, and induce universally true generalizations. With those universally true generalizations, one can eventually learn to apply deductions to propositions that increase a particular claim's specificity.

Later on, Aidan goes on to say the following.

“RL-based reasoners also don’t generalize to longer thought chains. In other domains, you can scale inference compute indefinitely. If you want to analyze a chess position, you can set Stockfish to think for 10 seconds, minutes, months, or eons. It doesn’t matter. But the longest we observe o1-mini/preview thinking for is around 10k tokens (or a few hours of human writing). This is impressive, but to scale to superintelligence, we want AI to think for centuries of human time.”

Do we want AI to think for centuries of human time? If reality were a deductive domain and you didn’t run into the truth issue, you would have a more significant problem in that the interesting thoughts in inductive domains don’t usually come from spending more time than is required to understand the idea.

In the words of John Boyd.

According to Gödel we cannot— in general—determine the consistency, hence the character or nature, of an abstract system within itself. According to Heisenberg and the Second Law of Thermodynamics any attempt to do so in the real world will expose uncertainty and generate disorder. Taken together, these three notions support the idea that any inward-oriented and continued effort to improve the match-up of concept with observed reality will only increase the degree of mismatch. Naturally, in this environment, uncertainty and disorder will increase as previously indicated by the Heisenberg Indeterminacy Principle and the Second Law of Thermodynamics, respectively. Put another way, we can expect unexplained and disturbing ambiguities, uncertainties, anomalies, or apparent inconsistencies to emerge more and more often. Furthermore, unless some kind of relief is available, we can expect confusion to increase until disorder approaches chaos— death

Boyd suggests a solution for this particular problem of inward-focused mismatch.

Fortunately, there is a way out. Remember, as previously shown, we can forge a new concept by applying the destructive deduction and creative induction mental operations. Also, remember, in order to perform these dialectic mental operations we must first shatter the rigid conceptual pattern, or patterns, firmly established in our mind. (This should not be too difficult since the rising confusion and disorder is already helping us to undermine any patterns). Next, we must find some common qualities, attributes, or operations to link isolated facts, perceptions, ideas, impressions, interactions, observations, etc. together as possible concepts to represent the real world. Finally, we must repeat this unstructuring and restructuring until we develop a concept that begins to match-up with reality. By doing this—in accordance with Gödel, Heisenberg and the Second Law of Thermodynamics—we find that the uncertainty and disorder generated by an inward-oriented system talking to itself can be offset by going outside and creating a new system. Simply stated, uncertainty and related disorder can be diminished by the direct artifice of creating a higher and broader more general concept to represent reality.

So, one might want to ask what the right amount of time to spend on a particular problem in an inductive domain is, but the issue is that the only way to know is by experiment. Starting with the wrong inductive priors and spending eons thinking about a problem will ultimately lead one to conclusions that have nothing to do with reality. In so much as one should use deduction, it affirms the correctness of one’s inductions by building systems of thought that become consilient as more inductions are explicitly added.

Aidan poses this question about an agent writing a philosophy essay.

“In high school, I wondered how to spin up an RL agent to write philosophy essays. I got top marks, so I figured that writing well wasn’t truly random. Could you reward an agent based on a teacher’s grade? Sure, but then you’d never surpass your teacher. Sometimes, humanity has a philosophical breakthrough, but these are rare; certainly not a source of endless reward. How would one reward superhuman philosophy? What does the musing of aliens 10 × smarter than us look like? To this day, I still have no idea how to build a philosophy-class RL agent, and I’m unsure if anyone else does either.”

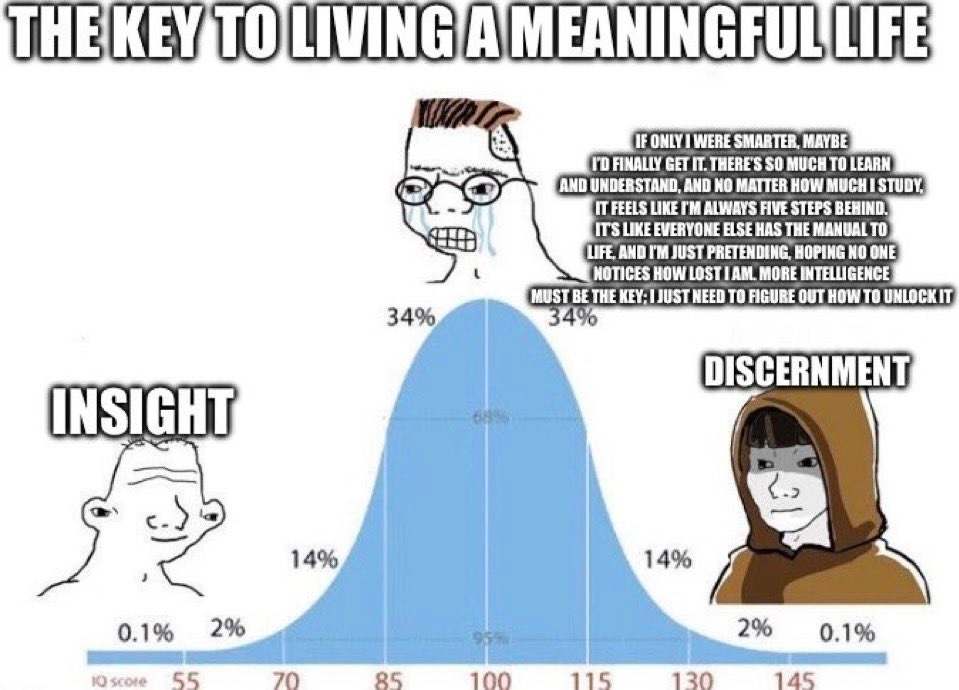

This thought process is flawed because it implies that philosophical breakthroughs come from genius. While it is true that otherworldly genius is nice for philosophy, experiments, and experiences are much more critical.

If the development of philosophy was to answer the question of multiplicity and change, then ultimately, what you need to solve these questions are discernment and lots of data to sample. The data that is sampled is used in the process I described earlier.

Instead, to arrive at knowledge, one must interact with the world, learn cause and effect, form concepts from percepts, and induce universally true generalizations. With those universally true generalizations, one can eventually learn to apply deductions to propositions that increase a particular claim's specificity.

To answer whether there are many things and if things change, one must look at the many things one experiences and how they interact. Through this inductive process, one eventually arrives at universally true generalizations. One difficulty is that this process usually happens intuitively and implicitly and is automatized. The philosopher's goal is to pull out these intuitions then and make them explicit.

Even with a bright, alien mind that can make his intuitions explicit, he is still left with the ultimate problem of inward mismatch. For many significant philosophical problems, there is no amount of inward search that you can use to arrive at the solution. Instead, he must rely on the history of civilizations.

To end it off, here is a quote from Leonard Piekoff

“The philosopher does not conduct laboratory experiments; he does not deal with test tubes, microscopes, or algebraic equations. The philosopher’s laboratory is history. Philosophic principles are tested in the historical record of human civilizations.”